One of the most catastrophic issues of the Anthropocene is the accelerating extinction rate of non-human life and the accompanying biodiversity crisis (Ceballos et al., 2015). The age of the sixth mass extinction is upon us (Barnosky et al., 2011), despite species conservation initiatives having become bolder and costlier since the 1960s. Within this paradigm, animals have taken on value as living creatures in their own right, as opposed to meat or assets for assisting human life.

Endangered wildlife is valued more and more – conservation is now a fully fledged industry and scientific field involving a large network of professionals (Schleper, 2019). In this regard, pioneering work has included relocating/reintroducing animals to places free from threats, and cloning or breeding nearly extinct species in captivity to stabilise numbers.

Preservationist ventures have transformed the value assigned to certain species and individual animals, with the prospect of extinction coming to galvanise scientists, animal collectors, and zoos. Rare species have become commodities for animal traders, part of the zoo trade, and features in world-famous projects. Charismatic large mammals, such as bison or tigers, have attracted lots of attention and funding (Albert et al., 2018), as opposed to equally endangered creatures like small amphibians. To attract funding, zoos have sought to make some of their animals into icons, as in the case of Ming Ming, the world’s longest-lived giant panda (1977–2011). There have also been narratives of prolific male ‘saviours of their species’, including the giant Galápagos tortoise Diego (1910s–).

In the 1970s, scientists realised that it was not enough to increase the sheer number of individuals in a species on the brink of extinction. A safe population needed to be not only large enough to sustain itself, but also genetically diverse. Since gene diversity within endangered species tended to be very low, animals with under-represented genes became valuable because of coming from less widespread lineages, unrelated to others.

The conservational value of an endangered species is evident in the example of Przewalski’s horses (equus przewalskii), celebrated as the last wild horse on our planet (Moehlman and King, 2018). In the nineteenth century, these animals were increasingly scarce – they went extinct in the wild in the 1960s under pressure from hunting, disease, harsh winters, and hybridization with domestic horses. A modest resurgence was made possible by a captive population bred in nature reserves and zoos across the world that descended from twelve horses – a tiny genetic pool – acquired from animal traders at the beginning of the twentieth century.

For many zoos at that time, the horses were ‘by far the most valuable and rare animal’, in the words of Adelaide Zoo’s Director Ron Minchin in 1938. The horses’ high value was linked to their scarcity and scientific appeal, as well as a romantic ideal of wildness. Imagined as stunningly galloping across Mongolia’s vast stony deserts, they were deemed a ‘missing link’, a living relic, domestic horses’ ‘wild ancestor’ – altogether a different animal, genuine and (seemingly) untainted. Despite this value and breeders’ desires to preserve them, it was nearly impossible to avoid inbreeding in the tiny population, which raised questions about whether low genetic diversity would prove lethal on account of hereditary diseases, birth defects, and fertility problems (Vasile, 2021). Therefore, capturing wild horses to ‘refresh’ the genes of the captive population became a priority.

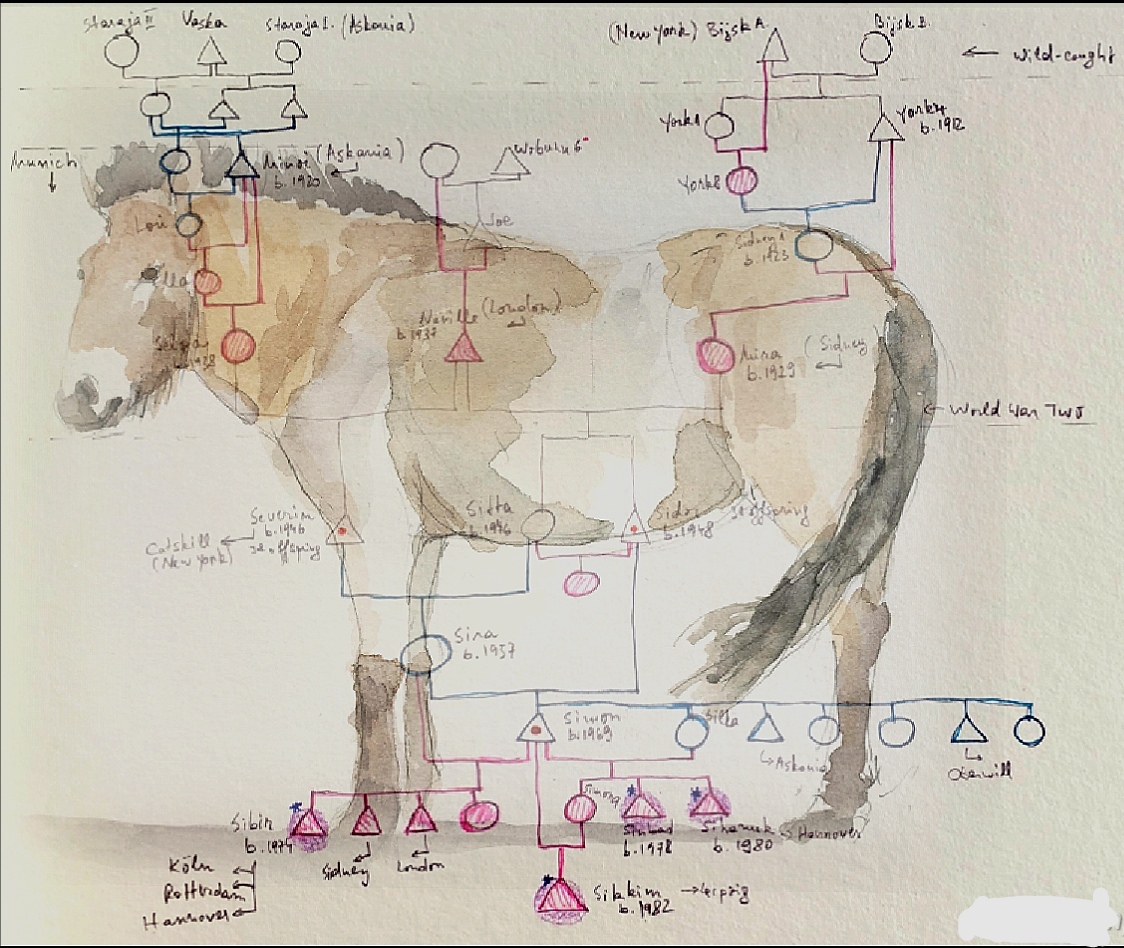

In 1957, the Mongolian government presented the Soviet Union with a wild-caught mare for its captive population. Orlica 3 (1946–73), also known as 231 based on her numbering in a studbook that recorded pedigree (Mohr, 1968), was very valuable. Without the lineage resulting from her, there would have been genetic impoverishment, more vulnerability to disease, and less adaptation capacity in the entire species. It was at a scientific breeding institute in the midst of a southern Ukrainian wilderness reserve, Askania-Nova, that Orlica 3 mated with a stallion imported from Munich Zoo. Their offspring and subsequent generations ended up all over the world, spreading ‘rare genes’ throughout a whole captive population, contributing to its recovery.

Przewalski’s horses were reintroduced into Mongolia in 1992. By 2021, the population had risen to more than 3000, half of which ranged freely across Mongolia’s steppes and deserts.

Questions

- How has the value of wildlife shifted in the course of the Anthropocene?

- How and why did it become paramount to ‘save’ species?

- To what extent was the prospect of massive biodiversity loss essential to human efforts to avert extinction?

- In the process of species conservation, what kind of values are created?

- How are individual animals and their lineages valued in terms of the survival of species?

Readings

Adams, W. M. (2004). Against Extinction: The Story of Conservation. Earthscan.

Albert, C., Luque, G. M., & Courchamp, F. (2018). The Twenty Most Charismatic Species. PLoS ONE, 13(7).

Barnosky, A. D., & al. (2011). Has the Earth’s Sixth Mass Extinction Already Arrived? Nature, 471, 51–57.

Boyd, L., & Houpt, K. A. (Eds.). (1994). Przewalski’s Horse: The History and Biology of an Endangered Species. SUNY Press.

Ceballos, G., & al. (2015). Accelerated Modern Human-Induced Species Losses: Entering the Sixth Mass Extinction. Science Advances, 1(5).

Kolbert, E. (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. Henry Holt and Company.

Moehlman, P., & King, S. R. B. (2018). Przewalski’s Horse. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. www.equids.org/aswhorse.php.

Mohr, E. (1968). Studbooks for Wild Animals in Captivity. International Zoo Yearbook, 8(1), 159–66.

Schleper, S. (2019). Planning for the Planet: Environmental Expertise and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1960–1980. Berghahn.

Sullivan, S. (2013). Banking Nature? The Spectacular Financialisation of Environmental Conservation. Antipode, 45(1), 198–217.

Tudge, C. (1992). Last Animals at the Zoo: How Mass Extinction Can Be Stopped. Island Press.

Vasile, M. (2021, 16 August). Incest at the Zoo: Saving and (In)Breeding the Przewalski’s Horse. Network in Canadian History & Environment. https://niche-canada.org/2021/08/16/incest-at-the-zoo-saving-and-inbreeding-the-przewalskis-horse.

Author: Monica Vasile