As a designation of our time, the Anthropocene is meant to call attention to how humanity’s changes to Earth’s geology and biosphere will have ramifications well beyond centuries of human civilisation. The processes by which humanity has set in train the Anthropocene are profoundly tied to economic systems and global geopolitics that attempt to cover up human and ecological violence, to distort distances, and to spread exclusionary notions of value. Such ‘modernity’ has consistently diminished oceanic textures and vibrancy. Krill fishing in the Southern Ocean is an exploitative industry belonging to the age of the Great Acceleration, following on the heels of the great industrial slaughter of Antarctic whales in the first half of the twentieth century.

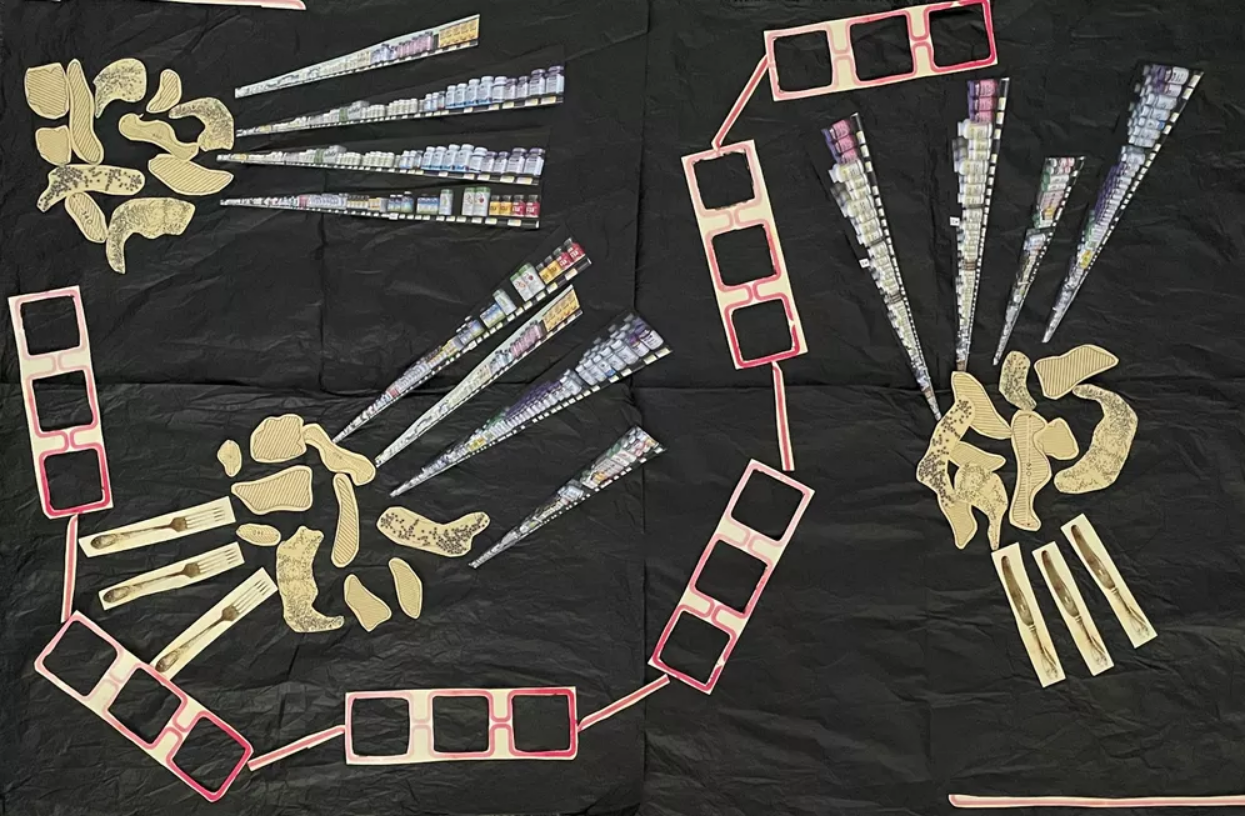

Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) is a small crustacean that lives in vast populations in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. Individually, a krill can grow to about six centimeters long and live for several years; collectively, Antarctic krill is perhaps the largest wild animal species on earth by biomass, with an average stock of around 380 million tonnes. And the rest of the Antarctic marine ecosystem—penguins, seabirds, seals, whales—relies on krill to live.

Despite the Southern Ocean’s tempests and Antarctica’s distance from most of the world’s population, the 1960s witnessed humans joining the list of krill’s predators. In the early decades of the Great Acceleration after the Second World War, fishing in the world’s oceans exploded, and the Southern Ocean was not immune from these pressures. Krill there were imagined to be a globally significant resource, one that might feed people lacking calories and nutrition in developing countries. The first krill fishing was done by the Soviet Union’s fleet, driven by a centrally coordinated socialist economy to grow and find resources to exploit. Other nations—Poland, Japan, Korea—joined in later years. Although the catch of krill from the 1960s to the 1990s fluctuated and never reached the dreamed-of heights of many millions of tonnes, in recent decades there has been steady growth, with Norway and China as today’s principal krill fishers.

Rather than feeding humans directly, the krill catch nowadays goes elsewhere. The nutrition industry values krill as a supplement: krill oil tablets, encased in plastic, line the shelves of pharmacies, supermarkets, and drug stores. Aquaculture fishing also values krill, since it can be fed to more commercially viable farmed salmon, which end up polluting waterways and communities worldwide. Both the nutritional supplements and aquaculture fishing trade in a discourse of better alternatives: krill oil is seen as better than regular fish oil, and farmed salmon is seen as a better alternative to red meat. But better for whom? Like so many products and commodities, krill entails hidden services, actors, (geo)politics, and communities.

The value of krill is also the subject of significant diplomatic and global negotiation. Since krill is central to the diets of much of the Antarctic marine ecosystem, over-fishing would have catastrophic consequences for other beings. Through the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources—a treaty-based international body of states devoted to managing fishing and conservation in the Southern Ocean—scientists and environmentalists argue about catching krill or not. In recent years, international environmental groups and certain nation-states have pushed strongly for greater marine protected areas (MPAs), seeking to further curtail fishingin the South. The idea of a ‘pristine’ or ‘relatively intact’ ocean, in comparison to drastically over-fished oceans elsewhere on the planet, is frequently invoked in this rhetoric.

As a designation of our time, the Anthropocene is meant to call attention to how humanity is making changes to Earth’s geology and biosphere that will have ramifications well beyond centuries of human civilisation. The processes by which humanity has set in train the Anthropocene are profoundly tied to economic systems and global geopolitics that attempt to cover up human and ecological violence, to distort distances, and to spread exclusionary notions of value. Such ‘modernity’ has consistently diminished oceanic textures and vibrancy. Krill fishing in the Southern Ocean is an exploitative industry belonging to the age of the Great Acceleration, following on the heels of the great industrial slaughter of Antarctic whales in the first half of the twentieth century.

In the past few years, the krill catch has been hovering around 300,000 tonnes. It is by no means an over-fished stock, and krill populations could arguably sustain a higher catch. It is a middling fishery by global standards, and many similar fisheries have been overworked. Like other Anthropocene dilemmas, there are ambivalences and tensions: humanity relies on the Earth to live through controlled resource exploitation, and perhaps certain under- or un-exploited more-than-human matter can sustain some demands; there are forceful discourses around ‘pristine’ and ‘wilderness’ areas, but we know that the whole Earth has been affected by humanity’s activities, and treating the Earth like a machine to tinker with has its own dangers.

Questions

- How do people or communities value what is distant, remote, or isolated?

- What kind of affective entanglements can humans build with krill and other distant creatures/environments?

- What does the Anthropocene look like at sea?

- How can we balance exploitation and protection?

- If human mobility across the Earth is a necessary precondition for the Anthropocene, should humans retreat to their localities, away from distant and remote Antarctica?

Reading

Alaimo, Stacy. 2017. ’The Anthropocene at Sea: Temporality, Paradox, Compression’. In The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, edited by Ursula K. Heise, Jon Christensen and Michelle Niemann, 153-61. London: Routledge.

Alaimo, Stacy. 2017. ’Unmoor’. In Veer Ecology: A Companion for Environmental Thinking, edited by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Lowell Duckert, 407-20. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Antonello, Alessandro. 2019. The Greening of Antarctica: Assembling an International Environment. New York: Oxford University Press [especially Chapter 4, “Seeing the Southern Ocean Ecosystem”].

Antonello, Alessandro. 2022. ‘Antarctic Krill and the Temporalities of Oceanic Abundance, 1930s–1960s’. Isis 113.2: 245-265. https://doi.org/10.1086/719745.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2017. ’Submarine Futures of the Anthropocene’. Comparative Literature 69.1: 32-44.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth. 2019. ’Toward a Critical Ocean Studies for the Anthropocene’. English Language Notes 57.1: 21-36.

Finley, Carmel. 2011. All the Fish in the Sea: Maximum Sustainable Yield and the Failure of Fisheries Management. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Finley, Carmel. 2017. All the Boats on the Ocean: How Government Subsidies Led to Global Overfishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCann, Joy. 2018. Wild Sea: A History of the Southern Ocean. Sydney: NewSouth Books.

Nicol, Stephen. 2018. The Curious Life of Krill: A Conservation Story from the Bottom of the World. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Rozwadowski, Helen M. 2018. Vast Expanses: A History of the Oceans. London: Reaktion Books.

Author: Alessandro Antonello