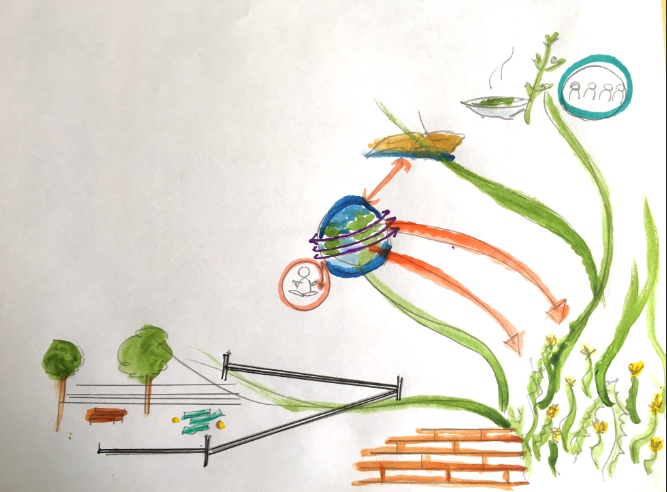

During long walks in the city I live in, I started to notice and photograph plants growing in fractures in the asphalt, on walls, or at the corners of roads and houses. The numerous images I took testified different ways in which nature manifests itself in urban spaces, flourishing in the interstices and disrupting the concrete. Monica Seger defines the “interstice” as ‘the gap between two objects of concrete meaning, the space between tissues in the body, the break in content of a printed text, the pause in time’ (2015, p. 4). Indeed, these manifestations grow informally in unofficial spaces, outside of the codified contexts of the ‘gardenesque approach’ to the city. As earlier urban nature regimes tried to overcome the clear-cut distinction between the city and the allegedly natural spaces of the countryside, they nevertheless maintained this differentiation by creating green areas as natural enclosed spaces in the urban context. Differently from these vegetated areas that require human planning, intervention, and maintenance – such as parks, recreational spaces, gardens, meadows, and lawns – nature in the interstice functions in a natural manner. Nature in the interstice, thus lets us reflect on the value of nature and non-human life – assigned and inherent – in the Anthropocene.

When these manifestations are not entirely disregarded, they are mainly defined and evaluated from a human perspective with reference to ideas on the natural that are often influenced by principles of spatial relevance, aesthetics, and usefulness. In opposition to these principles, these natural elements are referred to as “weeds” disrupting the discipline of the gardenesque. As Richard Mabey suggests, the most common definition of weed is that of ‘“a plant in the wrong place”, that is, a plant growing where you would prefer other plants to grow, or sometimes no plants at all’ (2010, p. 5).

However, new ecological approaches to urban landscape as well as some contemporary philosophies and practices – such as permaculture, urban gardening, and urban foraging – offer other perspectives. These disciplines interpret these manifestations as sources of food, opportunities to reconnect with ancestral knowledge and practices, and examples of resilience and resistance functioning as guiding elements in discourses on mental health and conscious living.

Questions

- What value can these spaces-in-between hold in discourses on the environment in urban contexts and within the Anthropocene?

- Does a debate on these spaces have the potential to trigger discussions about disrupting the prescriptive and predetermined spatial order attributed to nature in urban contexts?

- What experience of the natural environment do these spaces offer?

- What would a taxonomy of these plants reveal from a transnational point of view?

- How do communities interact with these spaces and natural elements?

- How are they represented and discussed in the arts?

Reading

Gilbert, O. L. (1989). The Ecology of Urban Habitats. Chapman & Hall.

Holmgren, D. (2017). Permaculture. Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Melliodora Publishing.

Iovino, S., Oppermann, S. (2014). Material Ecocriticism. Indiana University Press.

Kaika, M. (2005). City of Flows: Modernity, Nature and the City. Routledge.

Lachmund, J. (2013). Greening Berlin. The Co-Production of Science, Politics, and Urban Nature. The MIT Press.

Mabey, R. (2010). Weeds. How Vagabond Plants Gatecrashed Civilisation and Changed the Way We Think about Natura. Profile.

Seger, M. (2015). Landscape in Between. Environmental Change in Modern Italian Literature. University of Toronto Press.

Author: Laura Albertini